Nixon, Sadler: This Generation's Silver Dust Twins?

From Boston Baseball Magazine

PAWTUCKET, RI -- Before they became the Gold Dust Twins of the mid-1970s, Fred Lynn and Jim Rice made a pit-stop at Pawtucket for the 1973-'74 seasons. While it may be premature to make the following bold statement, let it be noted that Lynn and Rice never made it to The Show by being timid.

If Rice and Lynn were the Gold Dust Twins of their era, then it could be argued that Pawtucket second baseman Donnie Sadler and outfielder Trot Nixon are the Silver Dust Twins of their generation. Okay, maybe the Bronze Dust Twins would be more appropriate. This is a lofty comparison, sure, but an arguable one given the everyday-player development gulf between the mid-1970s and the Dan Duquette regime.

During the early 1970s, the Boston organization developed such stars as Carlton Fisk, Dwight Evans, Rick Burleson, Lynn and Rice. Since this burst of everyday-player talent, the Sox relied primarily on free agent acquisitions and trades during Lou Gorman's tenure as general manager (1984-'93). Then, during the early 1990s, another crop of home-spun talent appeared: Mo Vaughn, John Valentin and Tim Naehring. And of the three, only Vaughn commanded great accolades prior to his big league career at Fenway.

Red Sox General Manager Dan Duquette

Red Sox General Manager Dan Duquette

But since the arrival of Duquette as executive vice president and general manager, the emphasis has been placed back on the farm system. Hence, the much-anticipated arrival of Nixon and Sadler in Pawtucket. Nixon was the seventh overall pick in the 1993 draft, the first pick of the Duquette era, while Sadler quietly arrived at Single-A Fort Myers as a 10th-round selection a year later. The two didn't cross paths until they played at Trenton last summer.

"Those guys both played Double-A last year," says new Pawtucket manager Ken Macha, who managed both players last summer. "They both held their own in that league. They're being challenged here. Anyone can pick up these (poor statistics) and look at them. As far as I'm concerned, they've made tremendous strides. They've made great progress."

Both fit the profile of the natural, five-tool athlete, which has been the hallmark of Duquette's drafting career. Nixon squeezed the Sox for a then-record signing bonus by flirting with a scholarship offer to play quarterback at North Carolina State. In addition to his all-state shortstop career at Valley Mills (Texas) High, Sadler was a basketball point guard, a football running back and a track star.

Since their professional careers began, though, only Sadler has exceeded expectations. Nixon has battled lofty expectations and a chipped bone in his back, an injury that has stalled his progress.

Great Expectations

There were great expectations for outfielder Trot Nixon, Baseball America's 1993 High School Player of the Year, when he signed with Boston on August 31, 1993. Given his back injury, which was diagnosed in 1994, it's unfair to say he hasn't lived up to them.

Trot Nixon

Trot Nixon

"There are some pressures coming in," says Nixon in a Carolina drawl. "But as long as you're around good teammates that don't sit there and add to the pressure, it takes your mind off of (the pressure). You don't dwell on it."

This doesn't mean his mind doesn't wander. At times, he's wondered what life would be like as a college quarterback at a Southern school. "The only time that happens is when I'm struggling," he admits. "But when I go out there and I get a few hits, I'm not thinking about football. It's a great sport, it's fun, it's intense, but I'm happy."

Nixon is slotted for right field at Fenway. His defense has been solid, making a total of 11 errors in three years at four stops prior to this season. Most of his struggles have come at the plate, where he's cracked the .300 mark only once as a full-time player (.303 in 73 games at Single-A Sarasota in '95).

This year is no different, as he's having trouble finding the Mendoza Line. Through late May, he was batting .160 with four homers, 16 RBI and 22 strikeouts in 131 at-bats.

"Sometimes when you have failure, you can really get somebody's attention," says Macha. "Then they start to listen a little harder to what you're trying to say to them. ... I'm not worried about numbers. I want to see progress."

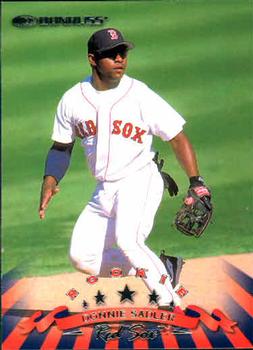

Speedy Sadler

Donnie Sadler

Donnie Sadler

While Boston expects Nixon to develop into a serviceable outfielder, the ceiling may be a bit higher for Sadler. He began his career anonymously with Single-A Fort Myers in 1994, but Sadler's 32 stolen bases in 53 games that season began a buzz in the system that hasn't abated. He added 41 stolen bases with the Michigan Battle Cats in '95, and then stole 34 in Trenton last summer. So far this season, he has 11 thefts, trailing only teammate Jesus Tavarez (16). Defensively, Sadler is a Hoover at second. Sadler owns tools that Boston hasn't seen in a player since second baseman Jerry Remy turned the pivot almost two decades ago.

The biggest challenge Sadler faces, he says, is the mental task of separating his offensive and defensive games. "Through that (offensive) struggling process, you can't let it affect your defense," says Sadler, whom Boston hopes will eventually form half of a formidable double-play tandem with Boston shortstop Nomar Garciaparra. "If you take your offense home -- saying 'I should have done this, I should have done that' -- it's going to affect your defense. If you can't help the team offensively, you have to be strong defensively."

He's hit in the mid- to high .200s during his career, much like Nixon. But a high average isn't what Boston expects from the five-foot, six-inch, 165-pound Sadler. What the organization expects is a high on-base percentage, so Sadler can work his magic on the basepaths. Statistically speaking, his special skills really became evident in 1995, when Sadler led the Midwest League in runs scored with 103 in 118 games played.

This year, Sadler overcame early season batting problems to compile a 14-game hitting streak that bumped his average to .225 from about .160. "Donnie has really come around," says Macha. "He's hit the ball in the middle of the field, he's starting to hit some line drives. There's been some improvement."

But at this stage of a young player's development, Macha reminds a clubhouse visitor, it's all about "learning how to handle your failures and push forward."

Post a comment