NFL Films: Keepers of the Flame

From New England Patriots Football Weekly

MOUNT LAUREL, NJ – Somewhere, in the misty region between love and madness, lies obsession. (With all due apologies to Calvin Klein.) And if not for the obsession Ed and Steve Sabol hold for the game of football, the National Football League might still be playing second fiddle to baseball as the national pastime.

Although it’s a symbiotic relationship between the Sabols’ company, NFL Films, and the league, the NFL and its players are eternally indebted to the father and son team from Philadelphia. Thanks to the Sabols’ obsession, love, passion, infatuation – call it what you will – with football, the men who play the game have been elevated from the mire they often play in to American myth. Johnny Unitas became a latter-day Apollo, Gale Sayers was transformed into Hermes and Dick Butkus became a 20th-century Ares.

During the past three-plus decades, NFL Films, a wholly owned but largely autonomous subsidiary of the league, has helped vault the NFL to the forefront of not only the American sports landscape, but the national consciousness. With its penchant for portraying the game and its players as larger-than-life events and characters – redundancy aside, the “frozen tundra of Green Bay” is among the most famous expressions in American sport – NFL Films has played no small part in the league’s march to the top.

The Sabols’ enterprise has played a key role in turning Monday Night Football into must-see TV, building the Super Bowl into an event that commands millions from Madison Avenue and boosting the league’s merchandise sales, all of which have transformed pro football into America’s No. 1 sport.

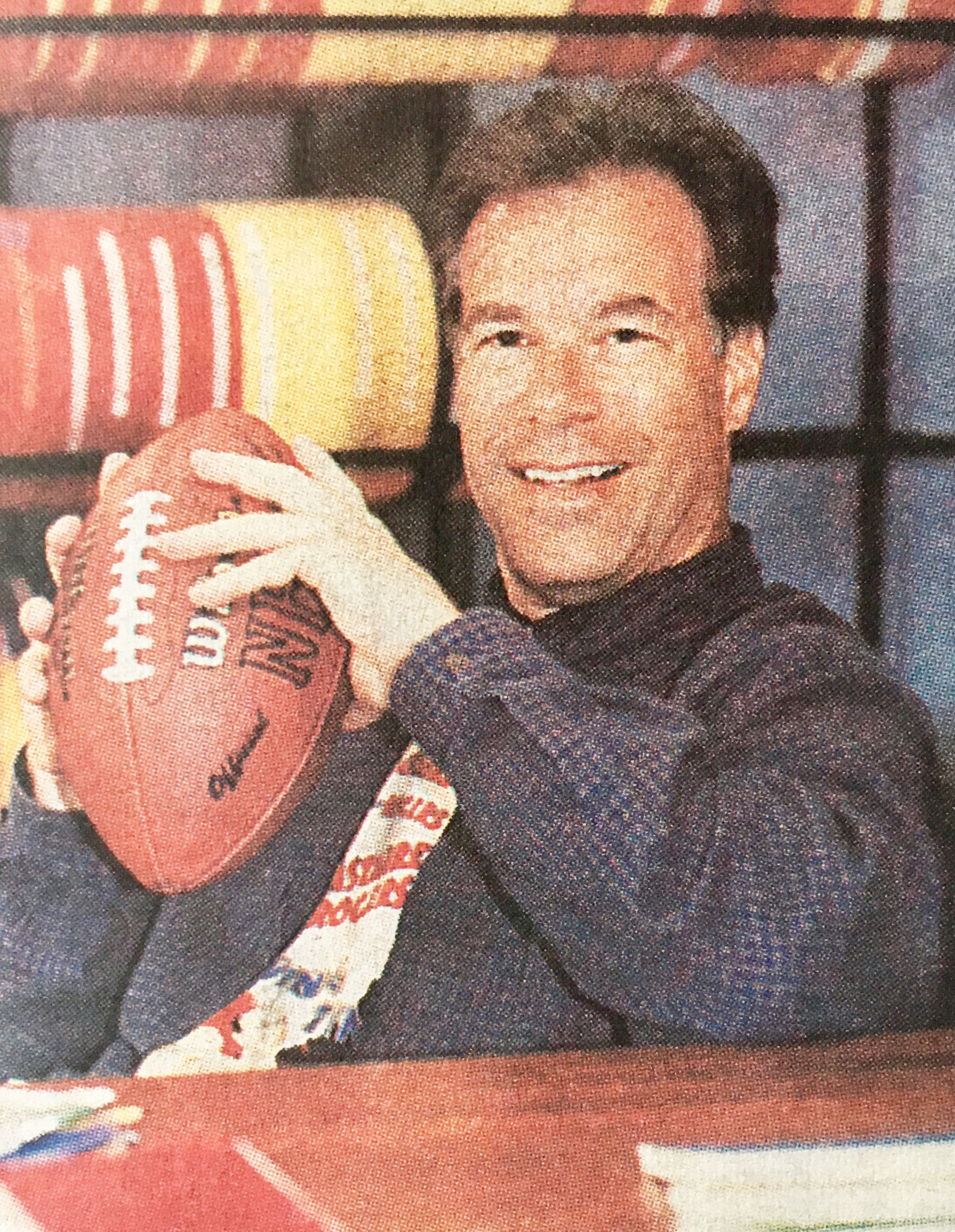

Steve Sabol

Steve Sabol

“I know [former NFL Commissioner] Pete Rozelle wrote my dad a letter after the big television contract [was signed] in ’85 and said that a lot of it was due to NFL Films’ image-making of the sport,” says NFL Films President Steve Sabol, reclining in his memento-strewn office in Mount Laurel, NJ.

Which begs the question: Would Napoleon Bonaparte’s overreaching military ambition have been rewarded is he had NFL Films in his corner? “If you look through history, a lot of the great historical figures had what they call ‘advocates,’ people who told their story,” says Sabol, decked out in the company mandated Oxford shirt, jeans and sneakers. "Natty Bumpo had James Fenimore Cooper. Where would Paul Revere be without Longfellow? [Biographer Mason] Weems told the story of George Washington and the cherry tree, which wasn’t true but became part of the myth. [James] Boswell told the story of Samuel Johnson.

“A lot of great figures in history have has great storytellers to accompany them,” adds Sabol, who started with the company as a camera man. “Our role is not just about one person; we tell the story of a whole sport.”

In addition to filming each game and producing highlight films for all 30 teams each year, the company produces a weekly syndicated show, NFL Films Presents, and HBO’s weekly Inside the NFL. NFL Films, which has 61 sports Emmy Awards littering the halls of Mount Laurel, also produces dozens of specialty highlight films and television specials each season. The company has also done work for the University of Notre Dame, NASA and has produced rock videos and various documentaries.

“The films are very upbeat and positive,” says Producer Suzanne Morgan, who handles the team highlight films. “You like to have a happy ending to your story, but only one of 30 teams gets that.”

In the Name of Love

There is little doubt that the Sabols have been the league’s biggest boosters during the past three decades. Granted, they’re on the payroll, but Steve insists that “Even if I wasn’t a part of the league, the films wouldn’t change.”

The Sabols didn’t set out to be myth makers or “keepers of the flame,” as NFL Films is often called, it just sort of happened. Like the company, which evolved into a multimillion-dollar enterprise without a business plan in the early years (“We didn’t know, from year to year, whether we were still going to be in existence,” recalls Sabol), NFL Films’ world-renowned style was a natural progression.

“It’s just an expression of the way we feel about the game,” says Sabol. “I think that when you look at the great movie makers, whether it’s Hitchcock, John Ford or Spielberg, the films are an expression, in many ways, of how they feel about something. Our films are always an expression of our love of the sport.”

Ed Sabol’s love of professional football in the early 1960s spurred him on to take a wild chance, which led to the birth of NFL Films’ predecessor, Blair Motion Pictures. The origin of NFL Films may be well-worn legend by now, but the story bears repeating, if only for dreamers.

An innocuous Bell & Howell eight-millimeter movie camera is perched on a glass stand in a corner of the company’s conference room. The room is packed with memorabilia – from ancient leather helmets to antique football board games to old, pebble-less footballs – so the camera would be easy to overlook if not for the assistance of a publicist.

That camera, Morgan explains, was a wedding gift to Ed Sabol, and the one that launched the company. No bigger than one of the neighboring leather helmets, the Bell & Howell recorded Steve’s gridiron exploits from youth football through his prep school days.

In 1962, with Steve at Colorado College (where, incidentally, the young running back lined up against then-defensive assistant coach Bill Parcells of Hastings College (Nebraska)), Ed faced a career crisis at age 45. His family’s company was sold and his job was gone. On a lark, he approached Rozelle, a publicity hound, and doubled the going rate for the rights to film the 1962 NFL title game.

Three thousand dollars earned Blair Motion Pictures the opportunity to film the New York Giants and the Green Bay Packers in the frigid cold at Yankee Stadium. On holiday break, Steve became part of the camera crew at his dad’s invitation. “My dad said, ‘I can see by your grades that all you’ve been doing is playing football and going to the movies. That makes you uniquely qualified for this profession.’”

Impressed with the quality of the film and the color, Rozelle welcomed the Sabols back in ’63 for the Giants-Chicago Bears championship game. The workload gradually increased, culminating in Blair shooting all regular season and playoff games in ’64.

At this point, fearing an interloper with deeper pockets, Ed Sabol again sought out Rozelle. Sabol convinced Rozelle that the NFL needed a motion-picture arm that would further the league’s cause. Rozelle seized upon the idea and huddled with owners at the team meetings. The 14 owners agreed to shell out $15,000 each, and nine months later the newly christened NFL Films rewarded each owner with a $25,000 check.

The NFL, which had long been an ugly stepsister to college football’s prom queen, and NFL Films were about to embark upon a beautiful relationship. NFL Films merely had to “promote the game and preserve the history of the game,” notes Sabol. “Those were the two mandates we got when we started.”

Ed (left) and Steve Sabol, surrounded by NFL Films' many Emmy Awards.

Ed (left) and Steve Sabol, surrounded by NFL Films' many Emmy Awards.

They were simple mandates, and ones that the Sabols have run with to this day. What’s allowed the company to not only succeed in its original mission, but to flourish, is the unique rapport shared by the Sabols. “My dad is not only my father, but he’s also my best friend,” Steve says of Ed, who’s retired to the Arizona desert. “He was the best man at my wedding, he’s the funniest person I’ve ever known and he also happened to be my boss.”

What sets NFL Films apart from its peers is that it’s run by artists, not business men. Understanding Steve’s imaginative bent, Ed gave Steve and his young colleagues artistic license to tell stories with a creative – not cookie cutter – flair. Ed handled business matters while Steve decided “how the films would sound, how they would look and to help with the photography.

“I guess I can go back to when I was an art major in college,” says Sabol. “You had certain artists who specialized in certain feelings. If you wanted a painting about the horrors of war, you’d go to Goya. If you wanted someone to paint about heroism, glory and courage, you’d go to Delacroix. I’ve always felt I’ve been more along those lines (Delacroix) as an artist.”

In addition to the music and pictures, Steve dabbled in writing. Steve easily could have plagiarized the alliterative style of the times – Milt plum pegs a peach of a pass to become the apple of coach George Wilson’s eye – but he didn’t want to fall into that pedestrian style.

The booming baritone of Philadelphia newsman John Facenda was a

The booming baritone of Philadelphia newsman John Facenda was a hallmark of early NFL Films productions.

He opted to write in sentence fragments. “We wanted to write less, not more,” Sabol remembers, preferring to let the film and the music works its magic. Enter John Facenda, a Philadelphia newscaster discovered by big Ed McMahon in his pre-Carson days. Known as “The Voice” to many, Facenda was blessed with a baritone capable of shaking redwoods – just what Ed and Steve were looking for.

Famous Sabol lines such as “the hands of combat;” “Lombardi: a certain magic still lingers in the very name;” and “they call it pro football: it starts with a whistle and ends with a gun” were made all the more immortal by the booming voice of Facenda. “That kind of writing was lifted to a whole new level when spoken by John Facenda,” says Sabol. “His voice was so important because when he spoke, you listened.”

Art and Profit

Sure, art is great, but you still need those dead presidents to pay the rent. Balancing art and profit is a challenge that few businesses face. Even NFL Films didn’t face this dilemma in the beginning, when housed above a Chinese laundry in Philadelphia before the move to Mount Lauren in ’78.

“If [the films] made money, good,” Sabol says. “As long as they didn’t lose money.”

When the league’s owners first agreed to fund NFL Films at Rozelle’s urging, this break-even proposition was implicitly stated by colorful Colts owner Carroll Rosenbloom, a fickle man who once traded the Baltimore franchise to Bob Irsay for control of the Los Angeles Rams in 1972. “I remember Carrol Rosenbloom telling my dad, ‘If you ever come back and ask us for more money, I’ll close your whole [expletive deleted] place down in a day,’” says Sabol.

Thus was born the partnership, albeit an uneasy one at first, between the league and NFL films. The owners were a difficult sell, but Rozelle convinced them of the wisdom of such a venture. The coaches? Suffice to say they weren’t big boosters of the concept. When asked if anything should be cut from the Packers’ 1966 team highlight film, Green Bay coach Vince Lombardi responded, “Yeah, the throat of the guy who wrote this crap.” Luckily, Steve survived the death threat.

Papa Bear George Halas instructed his octogenarian brother, Frank, to tail Steve in the early years, swearing that NFL Films was spying for the league office. During his coaching days, Norm Van Brocklin relegated NFL Films (and other media) to a muddy, roped-off pit during training camp.

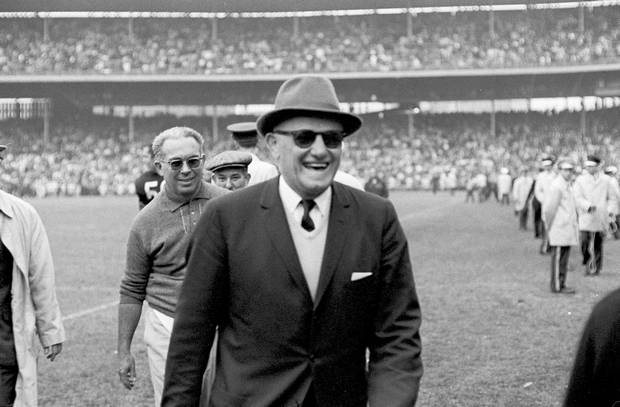

Legendary Bears coach George Halas was a vocal critic of NFL Films in its early days, but the Sabols eventually won him over and the irascible coach wrote that NFL Films was the "keeper of the flame" for professional football.

Legendary Bears coach George Halas was a vocal critic of NFL Films in its early days, but the Sabols eventually won him over and the irascible coach wrote that NFL Films was the "keeper of the flame" for professional football.

Halas once cackled about work that Steve had done on a Bears’ annual highlight film. “I [filmed] a ball being kicked into the end zone in Wrigley Field, and the fan who goes up to catch it puts his hands in the air and you can see a pistol in his belt,” says Sabol. “We put that in the highlight film, and Halas got really [expletive deleted]-off. ‘That’s not like Bears fans,’ he yelled. . . . Of course that’s exactly how Bears fans were in those days.”

The next year, in order to placate Halas, Sabol filmed well-heeled Washington Redskins fans and intercut those with Bears highlights. “This was before there was NFL Properties, so very few people were wearing identifying gear,” notes Sabol. “Up until the day [Halas] died, he said . . . ‘Those were the real Bears fans from Oak Park and the like, not those people you showed before.’”

The irascible Halas, as well as the others, gradually softened when they figured out what NFL Films was up to. How can you fight with people whose job is to elevate you to Valhalla? As he softened with age, Halas broke down and wrote a letter to Ed Sabol, calling NFL Films “the keepers of the flame,” a moniker that hangs on a banner in the company’s massive film vault.

Like Halas and Lombardi, NFL Films is itself a throwback. As indicated in its title, the company shoots on film and not on videotape (although it transfers the film to video for retail sales). Despite the multitude of firsts recorded by NFL Films – coaches and players wired for sound; ground-level slow motion; introduction of 600-millimeter telephoto lenses to sports; reverse-angle replays; blooper films; music specifically scored for sports; sports action edited to pop lyrics; and graphics to analyze game tactics – it is a traditional film house.

While working on a NASA documentary in 1978, Sabol and Phil Tuckett, now a vice president for special projects, collaborated with Orson Welles. “[Welles] said something I’ll never forget,” says Sabol. “He said that all true artists are either way ahead of their time or way behind their time. You can list all the firsts we’ve done, but now we’re the last to shoot in film. This is important because we’re romanticists and myth makers, and [film is] the right medium for that.

“If you went to see ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ and it was shot on videotape, it wouldn’t have the same sense of wonder and magic that film offers,” adds Sabol. “Film, in a way, is like wood. It has grain, texture, substance and history, whereas videotape is like Formica. It’s one level, one dimension and has no character.”

Post a comment