Bureau of Engraving and Printing Exhibit Highlights National Money Show in Boston

From Currents, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston's Employee Newsletter

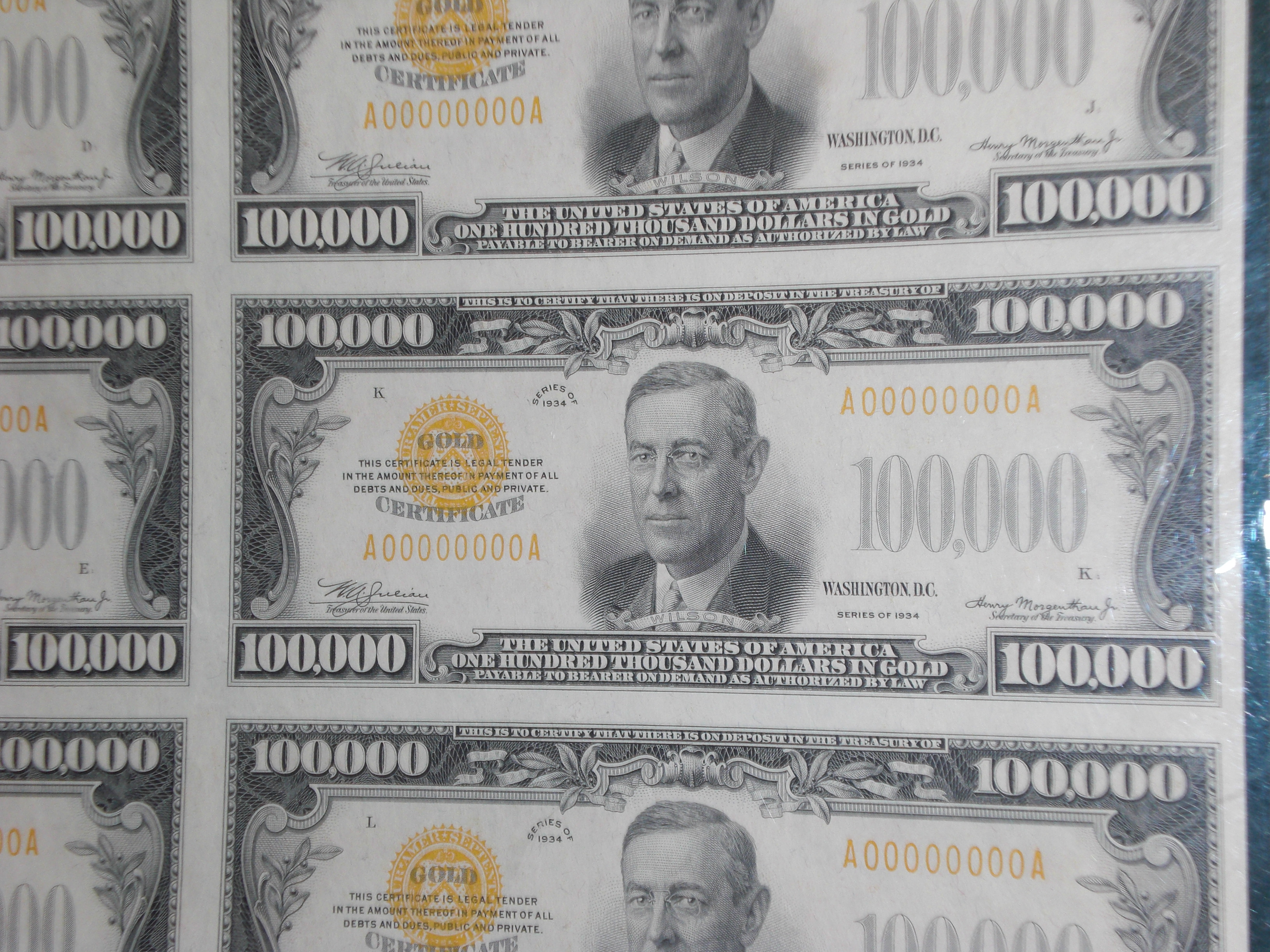

BOSTON – While the pristine uncut sheets of 12 $100,000 gold certificates were the most visually arresting paper currency on display at the World’s Fair of Money – the American Numismatic Association’s annual convention – it was the Bureau of Engraving and Printing’s modest mutilated currency display that offered the most intriguing tall tales at the Hynes Convention Center in August.

Sure, the $2.4 million worth of Woodrow Wilson notes, which were also on display at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) exhibit, were somewhat mesmerizing, but the stories behind the mutilated currency were emotionally engaging. Overlooking a case of burned, shredded, water-logged, moldy and dirt-encrusted U.S. paper currency, Eric Walsh of the Office of Currency Standards (OCS) patiently told tall, but true, tales about some of his department’s more offbeat redemption requests.

The OCS, you see, is the is the arm of the BEP charged with redeeming mutilated paper currency. While a teacher may cast a suspicious eye on “the dog ate my homework” excuse, “the dog – or cow – ate my money” is a relatively common claim heard by Walsh and his colleagues.

In one remarkable case, about 20 years ago, a gentleman’s cow ate his wallet, which contained $400. The man phoned the OCS, which instructed him to obtain the wallet, mail it in and the office would determine how much he was due.

Eric Walsh shared tall tales of currency mutilation at the show.

Eric Walsh shared tall tales of currency mutilation at the show.

Extraction details were left up to the claimant, who promptly “slaughtered his cow and sent the stomach – the entire stomach – to us,” noted Walsh, with an air of incredulity. Gamers that they are, the OCS specialists removed the wallet, counted the $400, and issued a Treasury check for that amount.

While most of the 30,000 cases the OCS handles annually rarely reach the Twilight Zone-level of the prior yarn, there are still many exciting, tragic and heart-warming tales attached to many redemption requests. According to Walsh, the toughest cases are handling damaged currency from natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina. “Water-logged money can harden into brick-like hard chunks,” said Walsh, banging a chunk of money against a display case window.

Disaster-zone banks, of course, will send in ruined money, but the human cost of such tragedies is most apparent when the OCS fields claims from ordinary citizens. “It’s very sad to see citizens sending in their water-damaged money,” said Walsh.

Conversely, Walsh is fascinated by “the challenge of handling burned currency from explosive armed robberies of ATM machines or armored cars.” People also mistakenly shred birthday cards with money inside, and animals often eat – and defecate – currency. The list goes on.

Perhaps the most rewarding cases are those where people stumble upon paper money buried by relatives during the Great Depression, or even the Y2k-inspired panic of more than a decade ago. “One person recently submitted a claim for $800,000 for buried money, but we’re nowhere near that amount at this point,” Eric added, chuckling.

Billion-Dollar Showcase

In a series of modest display cases, a few feet behind the mutilated currency, stood the BEP’s “Billion Dollar Showcase,” a collection of vintage U.S. paper currency, treasury notes and bonds. In one display case alone, the treasury notes and bonds totaled $1 billion. The other notes on display included a variety of rarely seen gold and silver certificates, Federal Reserve notes and national bank notes.

The back of the $100,000 Woodrow Wilson gold notes are very colorful.

The back of the $100,000 Woodrow Wilson gold notes are very colorful.

“People can’t get enough of the $100,000 bills,” said Kevin Brown, marketing manager for the BEP. “There were about 42,000 printed, and they were only used as a means of currency exchange for the Federal Reserve banks. They were never released into general circulation.”

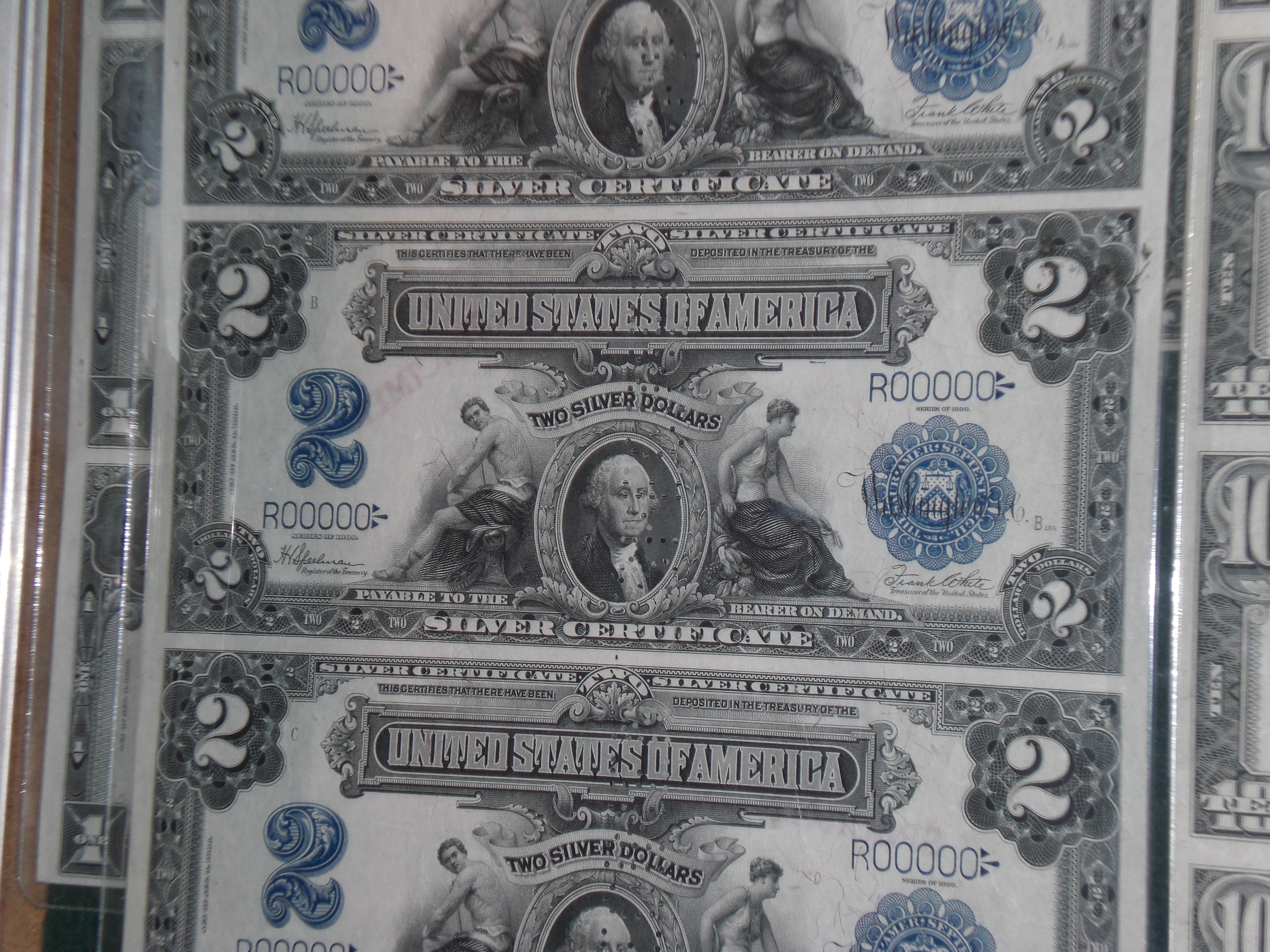

The Wilson $100,000 gold certificate may have been the king of the showcase, but the $100 Thomas Hart Benton gold certificate, the $10,000 Salmon Chase gold certificate (and Federal Reserve note) and the $5,000 James Madison Federal Reserve note were equally eye catching. Artistically speaking, a case can be made that the $2 George Washington silver certificate was the most beautiful of all the U.S. paper currency on display.

The $2 George Washington silver certificate.

The $2 George Washington silver certificate.

“We like to capture people’s attention with the ‘wow’ factor of our rare or mutilated currency exhibits, and then we can talk about our new currency and our latest counterfeiting technology,” noted Brown.

Currency engravers were also on hand to discuss their craft. Letter-and-script engravers serve as apprentices for seven years, while the apprenticeship of portrait engravers lasts a decade. “I often joke with the engravers that they’d have been better off going to med school because doctors can practice sooner than engravers,” said Brown, who also spoke about the BEP’s working 1860s-era spider press, which was also on display.

Other Show Highlights

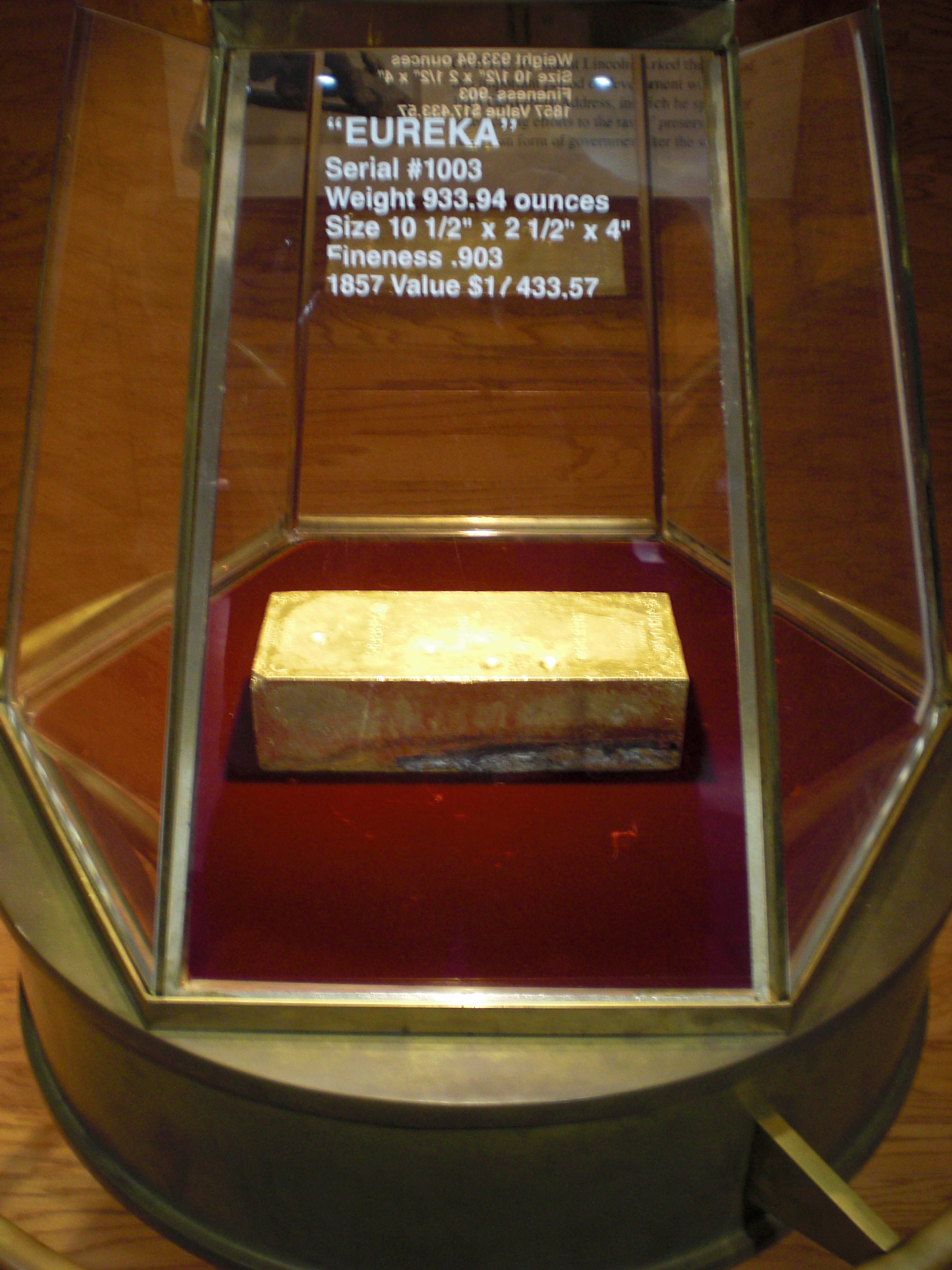

The largest surviving gold ingot of the California Gold Rush.

The largest surviving gold ingot of the California Gold Rush.

While paper notes played a role at the World’s Fair of Money, coins were undoubtedly the stars of this currency show. If one managed to escape the gravitational tug of the BEP area, there were hundreds of coin and paper currency dealers, coin clubs, educational seminars and collector displays scattered throughout the Hynes.

About a stone’s throw from the BEP booth rested the remarkable “Ship of Gold,” a mock wooden ship that displayed Gold Rush-era ingots, dust, coins and nuggets recovered from the shipwreck of the S.S. Central America, which went down off the coast of the Carolinas in 1857. The sinking of the S.S. Central America, which was carrying more than two tons of gold and gold products, led to the Panic of 1857.

One mammoth gold ingot, appropriately nicknamed “Eureka,” weighs in at almost 934 ounces and is the largest surviving ingot of the California Gold Rush. It measure 101/2 inches by 21/2 inches by 4 inches, and at today’s spot gold prices, the big brick can be conservatively valued at more than $1.13 million. Also on display are the remains of a wooden cargo box containing approximately 110 double-eagle gold coins. The stunning display was sponsored by Monaco Rare Coins, a California company that owns the rights to sell S.S. Central America treasure.

Just around the corner from the Ship of Gold was “Gold as Gold: America’s Double Eagles,” a Smithsonian Institution exhibit that displayed the first (1849 pattern) and last (1933) double-eagle gold coins produced in the U.S. Many coin collectors and historians argue that the St. Gaudens double-eagle gold coins, crafted in the early 20th century at the urging of President Theodore Roosevelt, are among the most beautiful U.S. coins ever produced.

Post a comment