Bill Russell Rules . . . Both On and Off the Court

From BJ's Journal, a publication of BJ's Wholesale Club

What do Emil Liston, Fuzzy Vandivier, and Joe Brennan have in common with Boston Celtics legend Bill Russell?

They were all inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame on April 28, 1975. What don’t they have in common?

Well, of the three men living at the time, Russell was the only one who refused to attend the induction ceremony. According to the March 1, 1975 issue of "The Sporting News," Russell said, “I’m not going [to the induction]. For my own personal reasons . . . I don’t want to be a part of it.”

That’s right. Russell, arguably the greatest player of all time (with apologies to Michael Jordan), blew off the Hall of Fame. But that was Russell then, only all too willing to tweak – if not yank – the nose of the establishment. “I knew Bill was his own man,” says Tom Heinsohn, a Celtics teammate and a fellow member of the hoop Hall of Fame. “It didn’t surprise me a bit.”

And neither should Russell’s dislike for authority. While a boy in Monroe, Louisiana, Russell and his family were often pricked by racial barbs. Russell’s father, Charlie, relocated the family to Oakland, California, when Russell was still young. “Freedom, a new form of freedom, lay ahead,” Russell wrote of the move in his 1966 autobiography, "Go Up for Glory." Although the Bay Area offered a more considerate climate for people of color, Russell still encountered racial injustice.

Things improved little when he moved to Boston.

“It was not a pleasant situation for Bill in Boston, and some of us never found out about some racial incidents until years later,” Heinsohn says. “I’m sure that racial issues did shape him.

“He was the first great black athlete to come to Boston,” Heinsohn adds. “He wins 11 championships in 13 years, and the city names a tunnel after Ted Williams.”

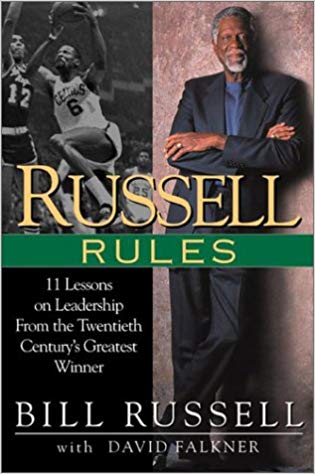

So, it might be considered ironic that the former center’s third and latest book, "Russell Rules: 11 Lessons on Leadership from the Twentieth Century’s Greatest Winner," will not only be read, but likely devoured, by the establishment types at whom he enthusiastically thumbed his nose as a young man.

After years of fielding questions about team play while on the corporate speaking circuit, Russell felt that it was time to divulge the principles of success that helped him win 18 championships in 21 years of organized basketball. “So what is this book about?” Russell asks in the "Russell Rules" introduction. “It’s about the skill sets, mostly mental and emotional, necessary for winning.”

Russell began to develop his skills in the pivot at McClymonds High in Oakland, where he played on three title teams. The beat went on across the bay at the University of San Francisco (USF), where Jesuit priests encouraged his curiosity in the classroom.

Curiosity plays a major role in Russell’s new book. The first lesson that Russell shares with readers is that commitment begins with curiosity. “What differentiates those who see and pursue the power of commitment versus those who can’t?” he asks in chapter 1. “One word: curiosity. Curiosity is as common as the air we breathe, but it is also the oxygen of accomplishment and success.”

Russell’s inquisitiveness – which was cultivated at an early age by his mother, Katie – carried over to the hardwood floors of USF. At a time when basketball was played horizontally, Russell experimented with the vertical game, using his great leaping ability to intimidate opposing shooters and revolutionize the game.

Phil Woolpert, his coach at USF, told "The New York Times Magazine" in 1957, “Actually, it’s difficult to measure Bill’s defensive value because much of it is psychological – a shooter hurrying a shot he shouldn’t take in order to avoid [Russell], or not taking one he should take.” Russell not only brought physical gifts – jumping and speed – to a center position previously occupied by lead-footed giants lumbering in molasses, but he employed a cerebral element that boosted his manual skills twofold.

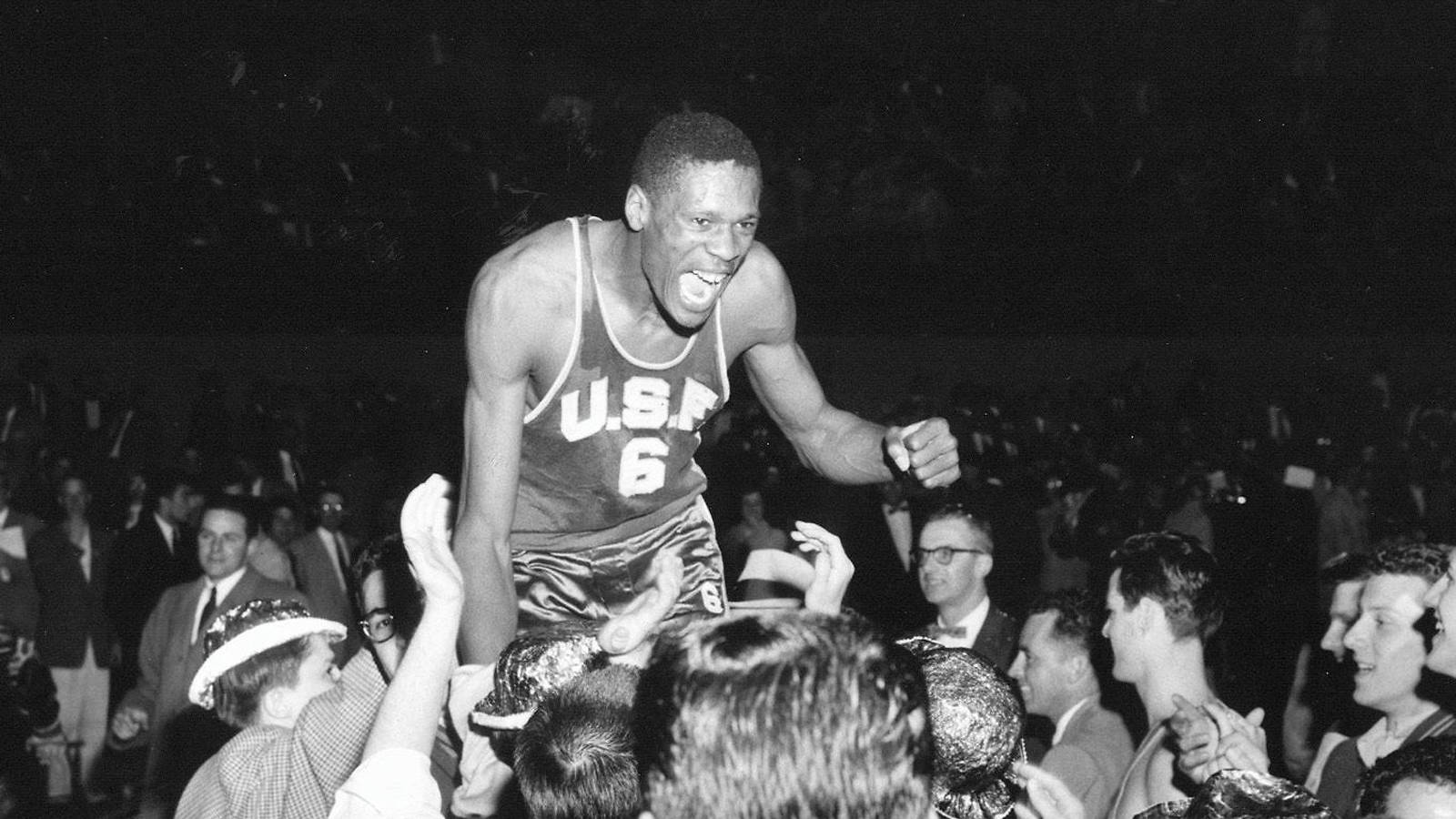

Since he was the first of a new breed, Russell had no on-court mentor. While at USF, he relied on future Celtics teammate K.C. Jones to help him experiment for countless hours. In chapter 1, Russell recounts how the pair created “a two-man laboratory on the court.” The results were devastating. The firm of Russell and Jones led the Dons to a divisional championship; a then-record 55 straight wins; and back-to-back National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) titles in 1955 and 1956.

Russell won back-to-back NCAA championships while at the University of San Francisco.

Russell won back-to-back NCAA championships while at the University of San Francisco.

“He was a great player [in college],” says Heinsohn, whose Holy Cross Crusaders once battled Russell’s Dons. “I mean I could beat anybody on the drive, get by him, and feel comfortable getting a shot off to the basket. I’d fake [Russell] out, leave him in the dust, and he’d be back blocking the shot. I never experienced that in my life before.”

After college, Russell took a detour to Melbourne, Australia, where he sparked the United States to an Olympic gold medal in 1956. Due to an affinity for Minneapolis Lakers center George Mikan, who once befriended Russell after a game in the Bay Area, Russell originally wanted to play for the Lakers. But Russell settled for the Celtics, who did some nifty maneuvering to obtain the rights to the 6’10”, 220 pounder. Russell’s impact was felt immediately by Boston, which was fast developing a reputation as a great regular season team that couldn’t seal the deal at playoff time. If the Celtics didn’t lose to the hated New York Knicks, it was the equally despised Syracuse Nationals who sent Boston home each spring.

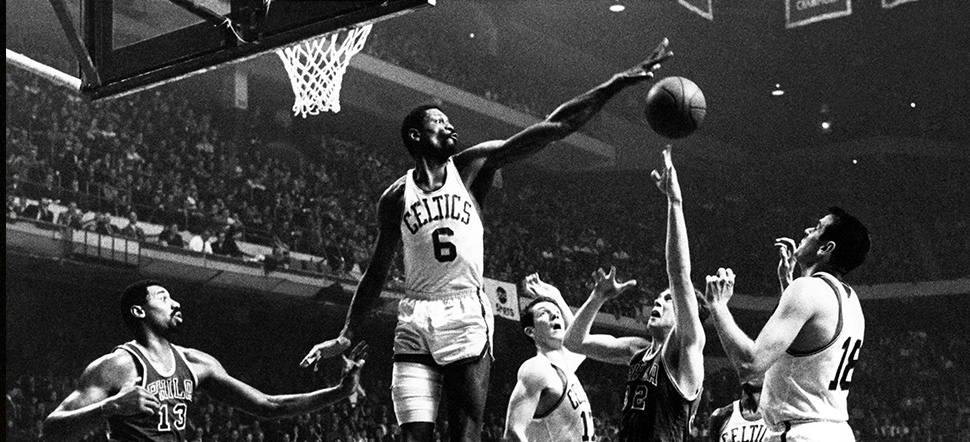

After losing to Syracuse in 1956, Celtics coach Red Auerbach told "The Boston Globe," “Damn it. With the talent we’ve got on this ball club, if we can just come up with one big man to get us the ball, we’ll win everything in sight.” Auerbach proved himself a prophet. In Russell, he found a big man who could not only rebound, but could block and deflect shots to his teammates to start the fast break (which Boston essentially invented). On the other end, Russell was less gifted, but still was able to subordinate what offense he did have for the betterment of the team.

Russell addresses ego in the second chapter of "Russell Rules," Ego=MC2. While countless writers, pundits and broadcasters proclaimed Russell the most unselfish player of his day, he says they couldn’t have been more wrong. “I was the most egotistical player they’d ever meet,” Russell writes. “My ego is not a personal ego, it’s a team ego. My ego demands – for myself – the success of my team.”

Professionally, that success began as soon as Russell hit the old Boston Garden parquet floor. Although he missed much of his rookie season (1956-57) due to the Olympics, Russell joined the Celtics in time to help them finally shed their postseason loser label. Boston took its first title that year, surviving a double-overtime seventh game against the St. Louis Hawks in the finals.

A year later, the Celtics fell when Russell suffered an ankle injury, but rebounded to win an unprecedented eight straight titles between 1959 and 1966. When asked if Russell “made him,” the inimitable Auerbach said in "Seeing Red," a 1994 biography, “In a way he did . . . . You got to be an idiot not to see that.”

After Auerbach retired at the conclusion of the 1966 season, Russell was named head coach, the first African-American to hold that title in professional sports. As a player-coach, Russell learned a lot about discipline, delegation and decision making, which he tackles in chapter 10 of Russell Rules.

In 1967, Russell’s first year as a player-coach, Boston was shredded by the Wilt Chamberlain-led Philadelphia 76ers in the playoffs. When Russell learned how to better manage the team, he led the aging Celts to two more titles.

During the 1968-69 season, Russell’s last, he noticed that the Celtics had lost 17 regular season games by three points or less. In order to rediscover Boston’s finishing touch for the postseason, he gathered the players and asked if any of them could recommend a last-second play from their college days.

Ohio State products John Havlicek and Larry Siegfried recommended one that Russell thought would work. The team whittled the play from 27 seconds down to four, and it helped Boston win five of its playoff games by three points or less. “The decision – which involved delegation, risk, commitment, discipline and responsibility – was, to me, the epitome of what sound decision making is all about,” writes Russell.

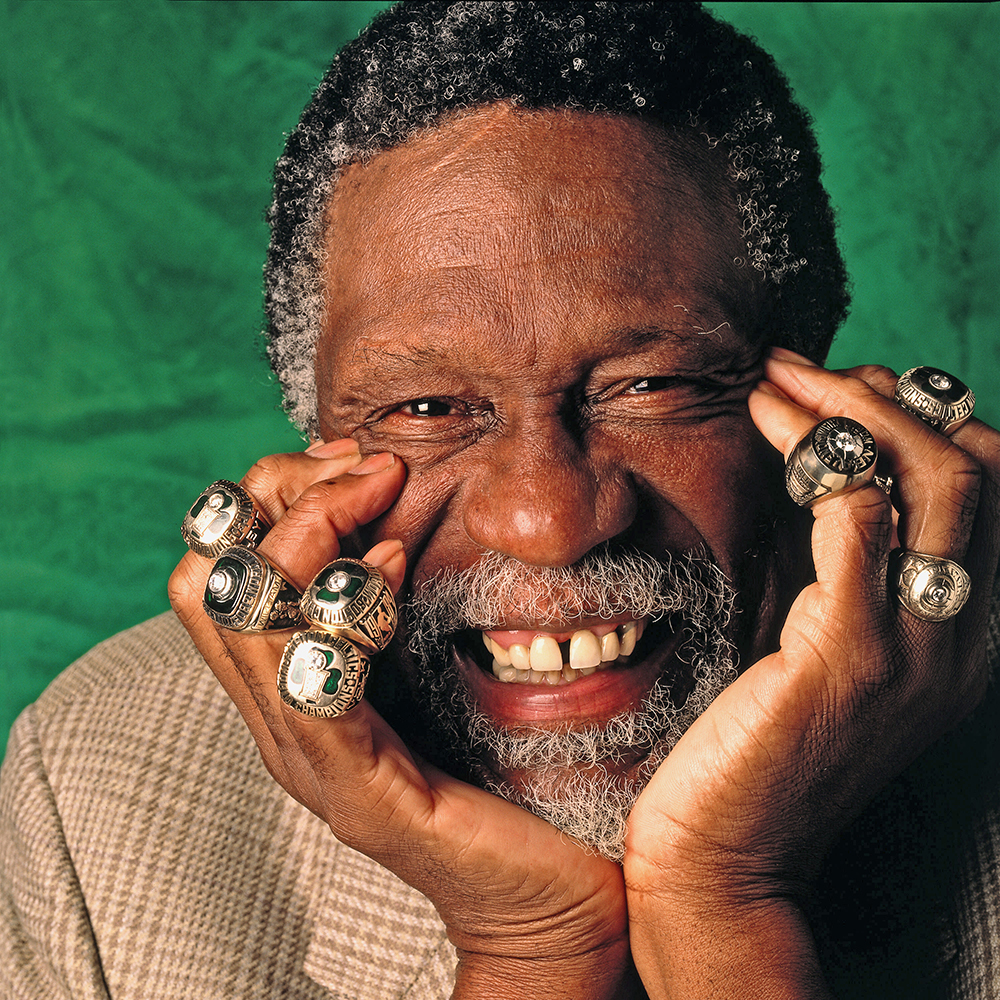

When he hung up his Boston tank top at the conclusion of the 1969 season, Russell had retired with more championship rings (11) than fingers, been named an all-star 12 times, earned five most valuable player awards, and established innumerable Celtics and National Basketball Association records.

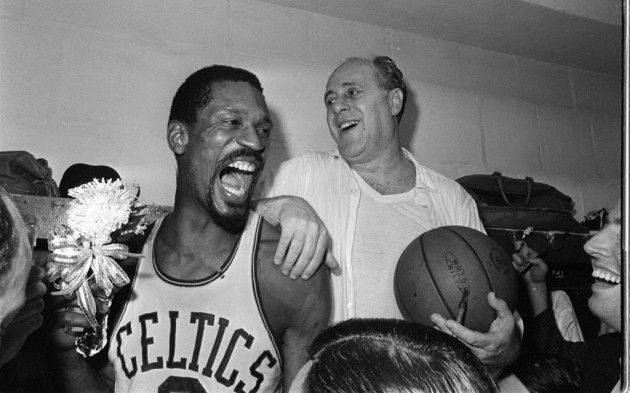

Russell and Auerbach set the standard for NBA championships.

Russell and Auerbach set the standard for NBA championships.

“Bill completely dominated the game from the defensive end,” says Heinsohn. “Nobody had seen the game dominated like that, and nobody’s seen it since. Bill refused to lose. When people did all the racist things that they did to him, he just answered by dominating the sport. Psychologically, he was a wounded person who became driven. I will tell you, he’s the most competitive person I’ve ever been around.”

While on the Florida leg of his book tour, Russell recently took a few moments to chat with BJ’s Journal about his book, his years with the Celtics, and his life away from the court.

BJ’s: After two autobiographies, why a new book? And why is it about leadership?

Mr. Russell: I speak at a lot of corporations, and in this book I address the most frequently asked questions I hear at these speaking engagements. Also, I wanted to talk about the Celtics and demystify the legend. I wanted to explain to people how it was for me to be a part of that very successful organization.

BJ’s: Why do you think that the 11 lessons outlined in your book are timeless?

Mr. Russell: The evolution process is very, very slow, so people now are pretty much like people were then.

BJ’s: What business leaders, people, and companies have best embodied the Russell Rules?

Mr. Russell: I mention a few in the book (Tom May, NStar of Boston; Larry Fish, Citizens Financial Group; Bill Gates, Microsoft; John Glenn; Starbucks; Harley-Davidson) and use them as examples of specific management styles. There’s a finite number of different styles you can use, but the style you choose has to be geared to your personality.

BJ’s: What is the most important Russell Rule?

Mr. Russell: There really isn’t one. These rules make a picture, like a jigsaw puzzle. You take one piece out and the puzzle is incomplete. Or if one piece is too prominent, the whole puzzle is thrown off; the picture is distorted. You know the cliché, ‘The devil is in the details?’ These things are a set of observations that allow leaders to get everybody involved.

BJ’s: In your new book, you mention that the road to commitment begins with curiosity. How has your sense of inquiry served you?

Mr. Russell: Well, when I was learning to play basketball, I was learning to play in a way that I had not seen. You see, I never had anyone say, ‘This is the way you do it.’ I had to use my imagination; I had to be curious, saying, ‘Let’s try this and see if it works.’ There was always a chance it would work; there was always a chance it might not work. But you always have to be curious. The reason I use [the word] curiosity is because you can’t be afraid to try things.

BJ’s: Did you apply your sense of curiosity to your life in general, too, especially after you retired from the Celtics?

Mr. Russell: That’s the way I live my life. When I stop being curious, they’ll just close the old cover on me.

BJ’s: Where did your sense of curiosity come from?

Mr. Russell: I got it from my parents. When we moved to California, one of the first things my mother did was get me a library card. She took me to the library, and made sure that I knew my way there and back. It was compulsory attendance. My father is my hero. One of the things he taught me is to respect yourself, respect others, and demand – or command – others to respect you.

BJ’s: Which leads to the next question. Who has influenced you the most?

Mr. Russell: Both my parents, because they gave different things to me. My mother always taught me to stand up for myself and never be a victim. My father always taught me to assess a situation before my first move. Assess a situation, take that information, and then decide what your move is going to be.

BJ’s: And speaking of assessing moves, how important was your great rival, Wilt Chamberlain, to your career, and do you believe that successful people or organizations need great competitors to drive them to greater heights?

Mr. Russell: Well, I don’t know if I’d say so. Motivation has to come from within, and you should always look to widen or broaden your horizons. Sometimes, there will be obstacles that are greater than others, but you must try to overcome those with the resources that are within you.

BJ’s: What type of player do you think you would have been if Wilt Chamberlain hadn’t played? Would things have been easier for you?

Mr. Russell: No, it would have been the same. A lot of folks say, ‘Well, one thing you accomplished is that your team beat Wilt’s team all the time.’ But we beat everybody’s team all the time. You can’t win championships by beating just one team; you have to beat everybody time and time again. Wilt was not only my friend but also a competitor. One of the ways I disciplined myself when he came into the league was not to change my game to play like him. I kept playing the way I had been playing to help my team win.

BJ’s: Ego is often considered a word with negative connotations. But in your book, you say that “team ego” is a positive motivating force.

Mr. Russell: I never think of ego as a negative. Ego is a neutral thing, but how you react to it makes it a positive or a negative. If you take my group, the Celtics, we were all highly egotistical individually. But, as I’ve said, all great organizations are benevolent dictatorships. You can’t have everybody making the decisions, and that’s where leadership comes in. This is when whoever’s in charge, male or female, has to say, ‘Well okay, now that I’ve collected information from all of you, I’ll assess it and I’ll make the decision.’ Then you’ve got someone to make the decision based on the information that they gather from the participants.

BJ’s: What’s the difference between team ego and personal ego?

Mr. Russell: Team ego consists of doing what it takes to make your team a champion, a winner. I could go out one night and get 35 points. If we lost, that would take some of the edge off [the personal achievement]. But if I go out, score 15 points and we win, I can’t feel bad.

You have to keep your personal ego within the context of the team; don’t suppress [personal ego]. I always wanted to be the best player on my team, but that didn’t mean I wanted my teammates to play less well. I wanted them to play as well as they could. We had an ego competition on the team, but as long as [players’ personal egos] were striving for the team ego, then it was healthy.

BJ’s: What are the top three attributes that players/people need to succeed?

Mr. Russell: Knowledge of their craft. Curiosity. Ambition.

BJ’s: What advice would you give today’s young athletes?

Mr. Russell: Try to master all the skills in whatever game you’re playing, and not just the obvious ones.

BJ’s: Who is your favorite athlete/sports figure?

Mr. Russell: Among guys my age, the first guy would be Jackie Robinson. Jackie Robinson was a highly intelligent man, and he always treated himself with respect and dignity. I always liked that.

My hero in high school was George Mikan. I met George Mikan when I was in high school. I was at a game, and after the game he came over and talked to me. It was so extraordinary how nice and gentle he was.

BJ’s: You’ve said that there are two of you: William Felton Russell of Mercer Island, Washington, and Bill Russell, star basketball player. What’s the difference between the two, and which Russell is the closest to the real you?

Mr. Russell: Well, “Bill Russell” is what I do. “William Russell” is who I am. One is my work personality; one is my “when-I’m-at-home personality.” When you’re out in the world, there’s constant motion. At home, there’s mostly peace.

BJ’s: Celtics fans appreciate what you’ve given to them and the game of basketball. Do you appreciate what basketball has given to you; a chance to travel, see the world, and live an extraordinary life?

Mr. Russell: I never think of basketball as having given me that. What I got from basketball was a game to play and to find out how well I could play it. But basketball was what I did. That never determined who I am or what I do with my life.

BJ’s: Did basketball give you a platform from which to speak about social issues in the 1960s, when you might not have had the opportunity otherwise?

Mr. Russell: I would have had the opportunity otherwise. I just would have. That’s the way I am.

BJ’s: You would have found an outlet?

Mr. Russell: You take guys like Jesse [Jackson], Martin [Luther King Jr.], and Malcolm [X]. They didn’t have a game to give them a platform; they created a platform.

BJ’s: How would you have created a platform? What would you have done with your life had you not played basketball?

Mr. Russell: I never thought about it, so . . .

BJ’s: After 18 championships in 21 years of competitive basketball, what was it like to retire?

Mr. Russell: I didn’t decide to retire all of a sudden; it was a slow process. You play until it’s time to stop.

BJ’s: How did you know it was time to stop?

Mr. Russell: I just knew. ‘I’ve done this enough,’ I thought. ‘It’s time to go and do something else.’

BJ’s: Have you found anything in your life as fulfilling as basketball since retirement? How did you fill the void of not playing basketball?

Mr. Russell: There was never a void. I’ve lived a full life. I never searched for something to do to pass the time.

BJ’s: You’ve lived a very private life for many years. Why have you embraced public life in recent years?

Mr. Russell: You know, it’s funny that people seem to notice what I’m doing now. But I’ve been doing the same things for years. People are just noticing it now. I think it’s because there are so many media outlets now, and people are looking for stories.

Post a comment