Aggressive Research on Steroids

From the Northeastern University Voice Faculty/Staff Newspaper

Since the electrifying summer of 1998, when Mark McGwire, a figure of Bunyanesque proportions, shattered Major League Baseball's 37-year-old home run record by clubbing an unheard-of 70, the hits, homers and records just keep coming. Last year, when bulked-up star Barry Bonds surpassed McGwire's three-year-old mark by launching 73 homers, America yawned.

With hitting records falling like dominoes in recent years, Sports Illustrated looked into the matter and in June, the magazine confirmed what observers had long suspected: That many pro baseball players abuse steroids and other supplements.

With youngsters watching their steroid-fueled heroes send baseballs into orbit, crush opposing quarterbacks, and set 100-yard dash records, more and more kids are turning to performance-enhancing substances, from steroids to androstenedione. According to Assistant Professor of Psychology and Behavioral Neuroscience Rich Melloni, more than one in 10 boys admit to using steroids.

Steroids quickly build muscle mass, but also cause horrific physical side effects, from liver and heart disease to sexual dysfunction. From a societal perspective, the most dangerous side effect of steroid abuse is violent and overly aggressive behavior, which Melloni and Ph.D. candidate Jill Grimes have been studying on the third floor of Nightingale Hall.

Steroids quickly build muscle mass, but also cause horrific physical

side effects, from liver and heart disease to sexual dysfunction. From a

societal perspective, the most dangerous side effect of steroid abuse

is violent and overly aggressive behavior, which Melloni and Ph.D.

candidate Jill Grimes have been studying on the third floor of

Nightingale Hall.

Grimes and Melloni have linked chronic steroid abuse with overly aggressive behavior in steroid-treated adolescent male Syrian hamsters. According to their most recent research, which was published in the October 2001 issue of Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, the aggression is caused, in part, by below-average amounts of serotonin, a brain neurochemical associated with impulse control.

"We're the first researchers to document the behavioral and neurochemical effects of steroid use during a critical period of development, adolescence," says Grimes. "The research we're conducting is very exciting and relevant in today's society, especially with the emerging issue of steroid use among Major League Baseball players.

"Kids look up to many sports figures," adds Grimes. "If teens think that there's a correlation between hitting the baseball out of the park and using steroids, there's a good chance that adolescents are going to abuse steroids, also."

According to Melloni, Syrian hamsters were picked for this research because of several human-like qualities. These hamsters:

will defend their territory against intruders;

will normally stop fighting before seriously harming another hamster;

and have a hypothalamus - an area of the brain that regulates aggressive behavior - similar to humans, according to unpublished data.

"Hamsters are a nice model to study, most notably because of the ability of this animal to switch from attacking and biting to flank-marking and scent-marking as a display of dominant status," says Melloni. "Well, humans also display dominant status without having to fight: shoulders back, chest out. Just watch guys at a bar on a Friday night."

Although Melloni and Grimes believe that many of the brain's neurotransmitter systems are involved in the aggressive response instigated by steroids, the pair's research has thus far focused on the serotonin and arginine vasopressin neurotransmitter systems.

"Well, humans also display dominant status without

having to fight: shoulders back, chest out. Just watch guys at a bar on a Friday night."

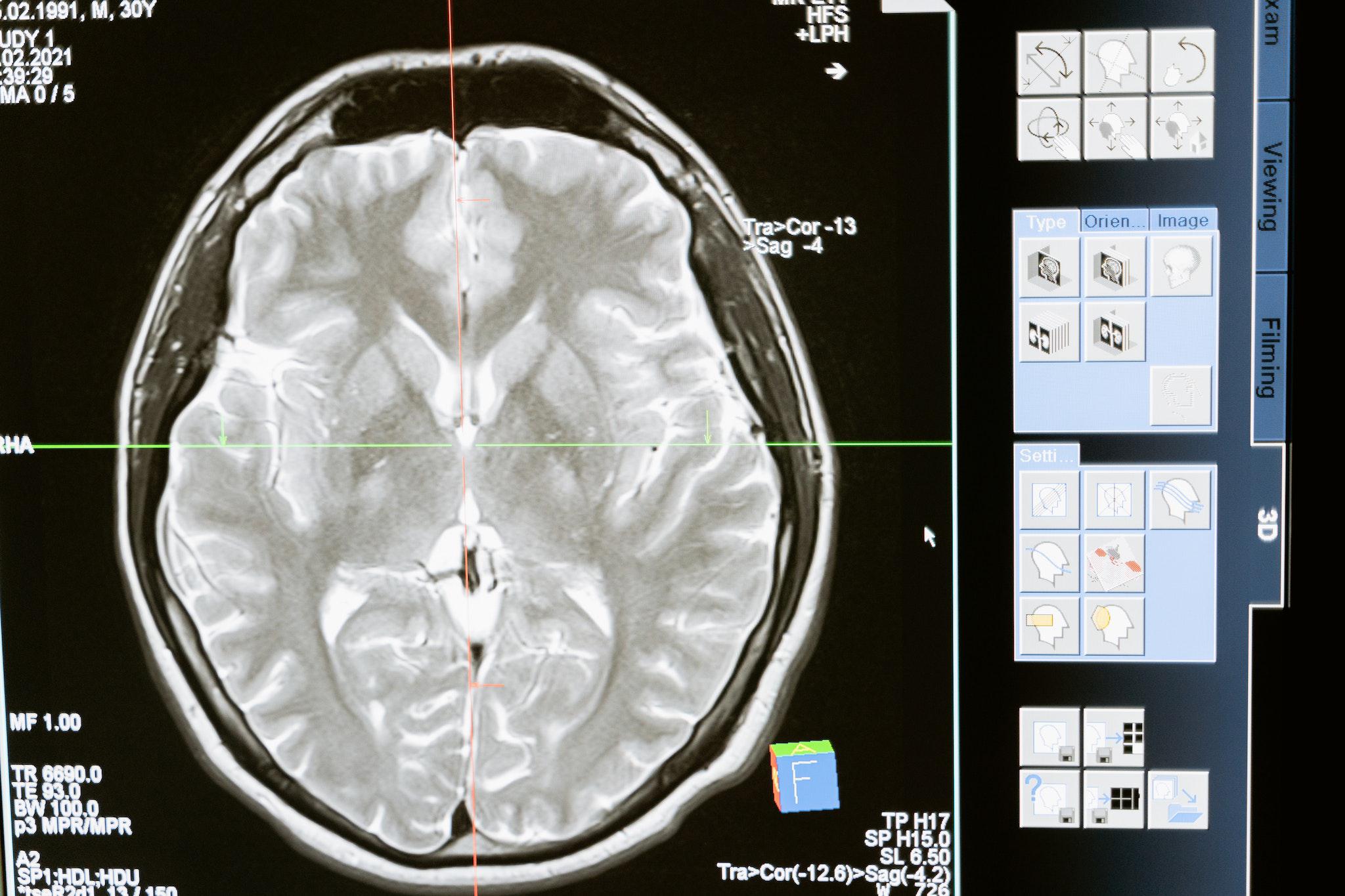

After studying the behavior and brains of steroid-treated adolescent hamsters and normal hamsters, the pair hypothesizes that serotonin acts as a brake on aggressive behavior. They also found that arginine vasopressin, another neurochemical, facilitates or encourages aggression. When compared with normal adolescent hamsters, those on steroids clearly have lower levels of serotonin in the anterior hypothalamus and in the medial amygdala areas of the brain. The steroid-treated hamsters also demonstrate elevated levels of arginine vasopressin in the anterior hypothalamus.

"Aggression is like a gun," says Melloni. "The neurochemical vasopressin is like a finger applying tension on the trigger, while serotonin is a finger that eases the tension. Our goal is to try to figure out what other neurochemicals - or fingers - are involved with the trigger, and their relative strengths."

Because adolescence appears to be a key time in the development of the serotonin system, steroid abuse during these years may impact a person's ability to assimilate into society. Steroid use, in fact, can radically alter a teenager's character, and may continue to cause violent or aberrant behavior long after usage ends. Whether these changes are permanent or not has yet to be determined.

"Determining the long-term effects of adolescent steroid exposure is one of our goals," says Grimes. "While our steroid research appeals to the scientific community, it also appeals to teachers, parents and, most importantly, adolescents who may be using steroids or thinking about it."

Post a comment